ABSTRACT

Cervical neck pain is a common presentation in primary care setting. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines cervical neck pain as “pain perceived as arising from anywhere within the region bounded superiorly only by the superior nuchal line, inferiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the tip of the first thoracic spinous process, and laterally by sagittal planes tangential to the lateral borders of the neck”1. Bogduk elaborates in his textbook the types of pains and the disconcerting habits of clinicians to inter change terms such as radicular pain and somatic referred pain1. Cervical radicular pain is “pain perceived in the upper limb” whereas radicular pain is “pain perceived in a region innervated by nerves other than those innervate the source of pain”. Another topic discussed in this paper is chronic whiplash associated disorder (WAD) secondary from whiplash injury. This is an interesting topic since as in New Zealand, the bulk of patients that present to musculoskeletal physician specialists are ACC (Accident Compensation Corporation) funded due to trauma. Whiplash associated chronic pain still seems to be a medical enigma to ACC and ostensibly leads to delayed patient care and dissatisfaction to both patient and clinician.

CASE HISTORY

Demographics: 38 year-old Indian male. Referred to musculoskeletal specialist clinic by general practitioner (GP) for assessment.

Presenting Complaint: Presents with six-month history of right sided neck pain and stiffness.

History of Presenting Complaint: Injured neck while attempting a back flip. Landed on right side of neck. Since then, the patient has been suffering from persistent right sided neck pain with radiation of pain down his right upper arm. Delayed presentation due to Covid-19 lockdown.

Past Medical History: Normally fit and well. Nil regular medications. No known drug allergies.

Examination: Reduced range of motion of cervical spine in all planes- flexion/extension/rotation/lateral bending. Tender right articular pillars with hypertonia of paraspinal muscles and tender points. Upper limb neurology essentially normal with right C7 dermatome altered sensation.

Impression: Probable somatic discogenic pain +/- C5/6/7 facet joint +/- somatic referred pain +/- right C7 nerve impingement.

Investigation: Xray showed no signs of fracture or dislocation. Loss of lordosis with vertebral end plate osteophytes. C6 anterior inferior end plate ossicle.

MRI- C6/7 right foraminal disc bulge and uncovertebral osteophyte causing mild to moderate narrowing of the neural foramen with moderate narrowing of the neural foramen and mild posterior displacement of the exiting right C7 nerve root. Mild cervical spondylosis between C3/4 and C6/7 with multilevel annular disc bulges and mild thickening of the posterior longitudinal ligament.

Management: Advised to avoid aggravating activities. Prescribed anti-inflammatory course. Referred to a musculoskeletal specialist for further input.

DISCUSSION

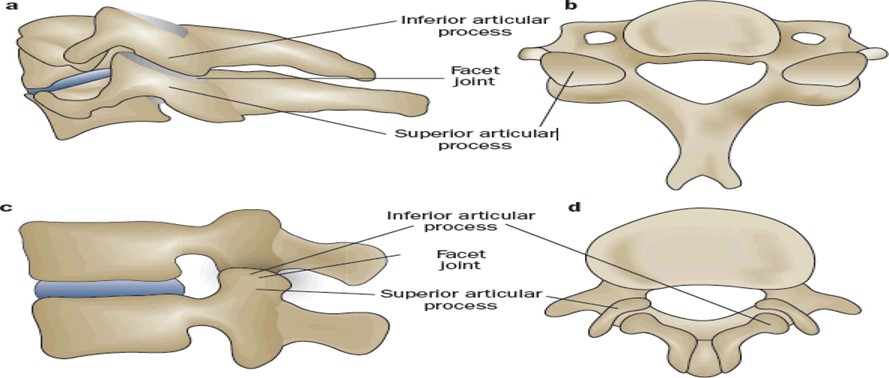

In this paper, special interest is placed on the facet joints. Facet joints are also known as zygapophyseal joints. These are intraarticular synovial joints and undergo the normal degenerative process as other intraarticular synovial joints elsewhere in the body. Unfortunately, these joints are often neglected in the orthopaedic surgical world. Facet joint pain is often chronic and harder to diagnose as it requires a good history, examination, and precision diagnosis. Invariably, insurers or funding institutions overlook this to prevent incurring costs associated with it due to its chronicity and complexity. It is often a long journey for the patient with delayed medical treatment before accurately being diagnosed by a musculoskeletal specialist. It is a cardinal sin to inadvertently attribute facet joint pain to psychosocial factors when in fact there might be peripheral nociception from the injured facet joint2. With the advent of radiographic imaging and musculoskeletal medicine armamentarium, Bodguk and colleagues have shed light to this “neglected” joint. It is getting more recognition in the medical world and chronic patients are finally getting the treatment they deserve.

James Taylor in his textbook describes the “three-joint complex” as consisting of paired facet joints and intervertebral disc2. The facet joints sit at an angle to each other, i.e., around 30-45 degrees2. Hence, these undergo load shearing forces when forces are applied on the vertebra.

The figure below illustrates the facet joint and its orientation2.

Bogduk in his textbook explains that no studies have identified the difference of response to the same treatment between patients with subacute neck pain from acute or chronic neck pain1.

Manchikanti L. et al. nicely elucidated in his paper the difference between somatic and radicular pain patterns3. He stresses that there has been an increase in the demand of cervical facet joint injections and neurolysis3. In Australia, Medicare claims have increased tremendously over the last 10 years raising the eyebrows of stakeholders, insurance companies and policy-makers3. Currently, there is Level II evidence of radiofrequency neurotomy and facet joint injections3. Complications from facet joint injections and medial branch of the dorsal rami are exceedingly rare. Some of the reported complications are soft tissue infection, nerve damage, vasovagal syncope, haematoma formation, vertebral artery transection, and spinal cord infarction secondary to emboli3. A systematic review carried out by Engel A. et al. stipulates that for safety reasons cervical medial branch radiofrequency neurotomy should be done under local anesthesia and not under general anesthesia to allow early recognition of potential complications4. A fully wake patient will be able to report any unusual sensations due to incorrect electrode placement4.

Dwyer et al. was one of the first to look at somatic referred pain mapping in the cervical spine5. He constructed pain maps perceived by normal healthy volunteers when their cervical zygapophyseal joints were injected intraarticularly with contrast medium5. The study showed noxious stimulation of cervical zygapophyseal joints produced pain patterns that radiated into the upper arm and scapula1. This study formed prima facie the acknowledging cervical zygapophyseal joint pain. Nevertheless, the validity and reliability of this study are questionable. This sparked other researchers in the later years to look at reproducing zygapophyseal joint pain. In 2007, Cooper G. and colleagues derived pain maps by relieving pain using local anaesthetic controlled blocks such as Lidocaine 2% (short acting) and Bupivacaine (long acting)6. Only a small amount of 0.3 mL local anaesthetic was used to anesthetize the medical branches of the dorsal rami to prevent bathing other anatomical structures that might confound the result. Since patients do not report neat patterns, grid densities were used to calculate the probability of pain reported in a particular area that might be attributed to a zygapophyseal joint6. C2-3 and C5-6 were the most commonly symptomatic zygapophyseal joints6. The conclusion from this paper was pain relieved by controlled blocks provide a more representative guide to the recognition of segmental origin of cervical zygapophyseal joint pain6.

Some emphasis is placed on the mechanism of whiplash associated injury. Bogduk in his textbook explains the step wise process of a whiplash injury1. Contrary to the traditional belief, he refutes the idea of whiplash being a flexion-extension injury. He describes the stepwise process of what happens during a typical rear-end motor vehicle accident1. The lower cervical spine flexes followed by an extension1. The centre of gravity shifts as the trunk moves upwards and shearing the facet joints. This can lead to injury of the following structures: bone, intervertebral disc, muscles, ligaments, nerves, vessels and most importantly the facet joints. Unfortunately, in this era of modern radiographic imaging, imaging such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) are unable to detect small lesions such as rim lesions, haemarthrosis or capsular tear of facet joints2. James Taylor showed in his autopsy of 109 patients that most injuries were in fact non osseous and not demonstrable on imaging2. More than 90% of post mortem radiographic imaging missed minor lesion such as rim lesions, capsular tears and haemarthrosis2. He stresses that soft tissue and ligamentous injury tend to heal quickly but articular cartilage damage is avascular and often leads to a pathological “degenerative sequelae”2.

There is a general misconception among patients that an MRI will pinpoint the exact source of pain. MRI might be good at showing other abnormalities e.g. normal age related degenerative changes, but this in itself might not be the source of pain1. To date, plain X-ray, Computed Tomography (CT) and MRI imaging have not been able to provide a valid diagnosis for a painful cervical facet joint4. MRI is good at excluding red flags for both the patient and clinician but often does not help tell the source of pain4.

One useful treatment option for chronic facet joint pain with good evidence backing it is cervical radiofrequency neurotomy. This involves using radiofrequency heat energy to coagulate the nerve fibres supplying the symptomatic facet joint, i.e. neuroablation7. Each cervical facet joint get its innervation from the medical branch of the dorsal rami, one each from above and below1. Hence, a successful block requires both nerves to be denervated to block nociceptive input7.

Prushansky T. and colleagues published a paper in 2006 studied 40 chronic whiplash-associated disorder patients and the outcome of radiofrequency neurotomy7. Although the paper has a few limitations, for example, the lack of control group and diagnostic blocks, the authors concluded that with a good history taking, examination and imaging, the outcomes for neurotomy is desirable at the one year mark7. This was further reinforced by other randomized controlled trials carried out in the latter years. As aforementioned, for a successful radiofrequency neurotomy, selecting the right patient population is essential. Lord SM. and colleagues looked at comparative local anaesthetic blocks and innocuous agent(normal saline) with placebo controlled8. The paradigm of two types of local anaesthetic blocks, i.e., short acting and long acting has been attractive for a long time. The conclusion drawn from the paper was placebo-controlled blocks are recommended from the medicolegal perspective or when surgery is being considered8.

The study by MacVicar and Borowczyk is an appropriate representation of this case study. Most of their patient cohort were trauma patients, with only around 5% of the subjects having degenerative related disease of the facet joint9. The study was rigorous with pre-set strict criteria, e.g., achieving almost 100% complete pain relief if the correct zygapophyseal joint was injected9. Although, we need to accept that there could be other sources of pain including the “culprit” zygapophyseal joint as the sole nociceptive pain generator, a stepwise approach of good clinical history and examination with radiographic imaging can usually help pinpoint the source of pain9. This is also backed up by a systematic review by Engel A. published in 2020 which emphasized the importance of stratifying the studies10. Statistically significant pain relief is achieved if patients are selected with complete relief from their index pain following comparative dual controlled blocks10. A negative study should not negate a positive study for RF neurotomy10. The selection criteria play a huge role in terms of determining the outcome of the study. If a study is poorly designed with laxed inclusion and/or exclusion criteria, it will lead to false study outcomes. Accepting poorly designed studies can lead to misconception in policy making.

Newer treatment options have cropped up with time. Pulsed radiofrequency neurotomy has attracted some attention by using full intensity radiofrequency but with cooling of needle tip with cold saline, or applying current in short pulses with rest intervals to allow cooling of surrounding tissues11. With the advent of this new RF neurotomy, there is lower risks of complications and the efficacy is maintained11. The time spent seems to be similar to traditional RF, i.e., 90 to 240 seconds11.

Invariably, patients with chronic neck pain tend to have central neurosensitization features. These patients tend to have widespread sensory disturbances and heightened central reflex symptoms12. A paper published by Smith AD. et al. tries to proof “augmented central nociceptive processing”12. The authors of the paper acknowledge that peripheral lesion might not be present on imaging, nevertheless, there is some source of peripheral nociception from the facet joint12. Radiofrequency neurotomy abolishes this nociceptive pathway. The study showed that by abolishing the nociceptive pathways, patients had better neck range of motion, reduced widespread hypersensitivity and central hyperexcitability12. This supports the notion of augmented central nociceptive processing12. There has also been studies in animal models where stretching of facet joint capsule can lead to the release of a cocktail of inflammatory mediators, causing peripheral sensitization12. The paper concluded that by reducing peripheral nociception causes changes in the central processing system, thus supporting radiofrequency neurotomy12.

CONCLUSION

Some “centralist” believe that chronic pain is not amenable from the treating the peripheral lesion due to central sensitization which is irreversible4. Often a psychological approach is recommended, while medical therapy is downplayed. This vexatious belief makes it futile for the treating medical clinician to help the patient. It should be a clinician’s modus operandi to offer the patient any possible treatment options available. Cervical radiofrequency neurotomy has shown some promising results with chronic pain patients being completely pain-free and being able to participate in their normal life again. Although this may be plausible, some chronic pain patients do not benefit from neurotomy and never seem to be completely pain free. Nevertheless, they have been offered a possible treatment option which every patient deserves. It is imperative as a clinician to understand that in the “pain world”, compromise is necessary, and that not accepting complete pain relief as a marker of success.

Reference

- Bogduk N, McGuirk B. Management of acute and chronic neck pain: an evidence-based approach: Elsevier Health Sciences 2006.

- Taylor JR, Taylor MM. Cervical spinal injuries: an autopsy study of 109 blunt injuries. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain 1996;4(4):61-80.

- Manchikanti L, Hirsch JA, Kaye AD, et al. Cervical zygapophysial (facet) joint pain: effectiveness of interventional management strategies. Postgraduate medicine 2016;128(1):54-68.

- Engel A, Rappard G, King W, et al. The effectiveness and risks of fluoroscopically-guided cervical medial branch thermal radiofrequency neurotomy: a systematic review with comprehensive analysis of the published data. Pain Medicine 2016;17(4):658-69.

- Dwyer A, Aprill C, Bogduk N. Cervical zygapophyseal joint pain patterns. I: A study in normal volunteers. Spine 1990;15(6):453-57.

- Cooper G, Bailey B, Bogduk N. Cervical zygapophysial joint pain maps. Pain Medicine 2007;8(4):344-53.

- Prushansky T, Pevzner E, Gordon C, et al. Cervical radiofrequency neurotomy in patients with chronic whiplash: a study of multiple outcome measures. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine 2006;4(5):365-73.

- Lord SM, Barnsley L, Bogduk N. The utility of comparative local anesthetic blocks versus placebo-controlled blocks for the diagnosis of cervical zygapophysial joint pain. The Clinical journal of pain 1995

- MacVicar J, Borowczyk JM, MacVicar AM, et al. Cervical medial branch radiofrequency neurotomy in New Zealand. Pain medicine 2012;13(5):647-54.

- Engel A, King W, Schneider BJ, et al. The Effectiveness of Cervical Medial Branch Thermal Radiofrequency Neurotomy Stratified by Selection Criteria: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Pain Medicine 2020;21(11):2726-37.

- Liliang P-C, Lu K, Hsieh C-H, et al. Pulsed radiofrequency of cervical medial branches for treatment of whiplash-related cervical zygapophysial joint pain. Surgical neurology 2008;70:S50-S55.

- Smith AD, Jull G, Schneider G, et al. Cervical radiofrequency neurotomy reduces central hyperexcitability and improves neck movement in individuals with chronic whiplash. Pain medicine 2014;15(1):128-41.